The Literature of Restoration

- The Literature of Restoration actively seeks through form and language, content and focus, to create and inspire a cultural shift, developing a body of literature that radically seeks the restoration and vitality of the natural world. It is concerned with the climate crisis, environmental destruction, extinction, the factors creating global, social chaos and the ways that Western and other contemporary imperial cultures inadvertently promote these conditions even while the themes may be opposite. Close scrutiny of self, language, cultural and literary standards is required to help us avoid reinforcing the trajectories we are on toward the destruction of all life. When the natural world, the environment, ethics, spiritual awareness and regard for the vitality of the future for all beings are at the center, as with Native American and Indigenous literatures, any subject may be pursued because the embedded intrinsic values that support all life are fundamental.

- As English tends toward the combative and bellicose, we need to scrutinize our words to shift the subtle communications which may well undermine the text and the writers’ basic principles. English considers conflict, combat, war, enemies, winning, victory, defeat and loss, competition, money, hierarchy, property, acquisitiveness, ownership as pervasive and inevitable. A central conflict is deemed intrinsic to a story while for other cultures and the Literature of Restoration, relationship, resonance, inter-connections, are basic as are cooperation and alliances in lieu of war, council forms over competition, common use, as in the commons, rather than private ownership. Euro-American culture exudes Calvinist, capitalist assumptions where the Literature of Restoration is concerned with the eros of community and cooperation, what gathers together rather than sets apart.

- It is difficult for Indigenous speakers to convey their deepest thoughts or to translate them into English as it lacks many equivalents for what is most intrinsic to Indigenous wisdom, particularly the understanding of mitakuye oyasin, all my relations, and the spiritual reality of the universe; the Literature of Restoration suffers similarly and attempts to remedy this.

- The Literature of Restoration seeks ways that new forms, language and story can guide us to a world which is vital, diverse, interpenetrating, inclusive of the rational and the wondrous, science and dreaming, rigorously aware of the dangers we face and our complicity in creating them. The Literature of Restoration bears witness, disconnects from the deadly forms of the Anthropocene and seeks vision for these times.

This essay is very hard to write. I have been struggling to find the words for a year. Over these months, it has sometimes seemed impossible to write about a new literature in an old language that is not serving us. The task before us is critical. There are questions to be addressed. I don’t know how to do this. Whatever I write, it will only be a beginning. Quest with me. As always, we have to do this together.

I don’t want to blame the language for my failures, but the difficulties with the English language are what I am writing about. I want to see if language and literature can be peacemakers. English is a combative language, which objectifies and separates. War, battle, conflict, competition, individualism, self-interest, materialism, objectification, righteousness, and victory, as well as the superiority and ‘rightful’ dominance of humans over non-humans are conditions and values embedded in English, and so Western culture, or in Western culture and so in English, and so this tragic moment in history.

I was once surprised by the contradiction of a colleague’s repeated use of “I argue” in his paper on traditional healing rituals in Sri Lanka. Perusing anthropological journals, I became aware that conflict, self-promotion and competition are common to academia. Let me be honest here – he was a man I loved and love does not imagine polarization. The term alerted me to a rift that became a divide that our connection couldn’t encompass. We separated.

***

Extinction stalks us. Not an act of God, but a consequence of how we have chosen to live our lives. Such choices are handed to us by language and literature. Literature that is reduced to media, obsessed with violence, conflict, sensationalism, nationalism and speciesism. We are each responsible – we participate – no exceptions. The antidote for extinction is restoration. Languages and literatures that lead toward restoration are essential. So we have to try ….

***

Looking for a Literature of Restoration, looking to restore values to English, questions arise. What if we don’t speak or write in other languages? What we if don’t know an Indigenous language? Can we solve the problems we are facing from the level of the problem?

As this is the language we speak, we must find the way.

When I wrote The Woman Who Slept With Men to Take the War Out of Them, I asked myself, Can we go to the General without using the weapons of the General?

Can we address the problems with English, from within English? Can we write about a literature of restoration before the words are written? When there is only the hope, though based on the efforts of many of us, to call forth a culture that will assist in saving the planet? This is what is at stake: the planet, the earth, all life.

Language embodies a culture’s perception of the nature of the world. This is communicated to us when we are children learning the basic meanings, implicit and explicit, of each word. As we mature, we learn that words are resonant with complex associations and allusions – undertones and overtones. Born into a particular language and culture, we develop according to inherent values, possibilities and restrictions.

On February 1, 2015, I dreamed a healing circle in my physician’s office. I reassured those in the circle that they knew the way of healing. Every time they sat in circle, every time they brought something down from the hill, every time they used a natural object, they learned the way of healing. Healing came forth when they gathered together to heal.

On February 1, 2015, I dreamed a healing circle in my physician’s office. I reassured those in the circle that they knew the way of healing. Every time they sat in circle, every time they brought something down from the hill, every time they used a natural object, they learned the way of healing. Healing came forth when they gathered together to heal.

Telling a dream about healing may bring restoration closer.

I was born into Yiddish. When I went to Kindergarten, I discovered Yiddish wasn’t the national language. Just before my mother died, she told me that the teacher had called her to school because I never spoke. My mother said, “She doesn’t speak English.” A familiar immigrant story – they didn’t want me to be ignorant of Yiddish culture and its language. After World War I, coming to the US, saved their lives but not their souls. Their hearts and souls remained in the language and the community – their lifeline.

My father was a Yiddish writer, translating his own work into English, or writing in English and translating into Yiddish. I never learned the nature of his struggle to negotiate between one and the other, but I sensed, though I never spoke Yiddish again, that entirely different worlds emerged from each. From the perspective of an outsider, which I have become, Yiddish allows for a lot of humor, which we sorely need in this world of holocausts, genocide and extinction; we need humor the way we need breath, water, bread and beauty.

Each language offers a particular gift. I want to use the Yiddish word, tam, here. Yiddish has a particular tam. Meaning something like an emotional, philosophical flavor and taste. We experience the tam and are attracted to the language. Honey on the tongue.

Many African languages depend on proverbs; they communicate wisdom in these tiny stories. I hear an emotional difference when my Spanish speaking friends speak to each other in their mother tongue, in their mother tongue, so much sweeter, cariñoso.

In the last years, Native Americans have begun to teach us the values intrinsic to the languages they speak. We can’t know what they know without speaking their languages. But what they write, though in English, takes us to new and profound understandings about the true, intrinsic nature of the world. Not what we manufacture – what is there.

Quantum mechanics gives us a fundamentally different view of reality and Indigenous languages reveal another reality as well. Lately scientists, physicists and Indigenous elders have gathered to find alliances in their world views. Maybe each is seeking to publicly substantiate itself through alliance with the other. However … quantum mechanics took us to Fat Man and Little Boy, the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Quantum physics has also taken us, most recently to Japan – again – to Fukushima. Indigenous languages take us to a profound and pervading love of the earth and respect and devotion to the spirits. I don’t think the two emerge from the same reality. Some might say quantum mechanics and physics didn’t create nuclear weapons. If quantum mechanics is a language of connection, why then split the atom?

Let’s hold all the questions and scrutinize our lives and what we write. Let’s not answer the questions, just keep adding questions and holding them.

As we consider bringing things together, rather than splitting them apart, let’s consider what Robin Wall Kimmerer writes. She notes that the Anishinaabe language does not divide the world between he, she and it, but between animate and inanimate. This distinction asserts an entirely different world:

“Imagine your grandmother standing at the stove in her apron and someone says, “Look, it is making soup. It has gray hair.” We might snicker at such a mistake, at the same time that we recoil. In English, we never refer to a person as “it.” Such a grammatical error would be a profound act of disrespect. “It” robs a person of selfhood and kinship, reducing a person to a thing.”

“And yet in English, we speak of our beloved Grandmother Earth in exactly that way, as “it.” The language allows no form of respect for the more-than-human beings with whom we share the Earth.”

… “In our language there is no “it” for birds or berries. The language does not divide the world into him and her, but into animate and inanimate. And the grammar of animacy is applied to all that lives: sturgeon, mayflies, blueberries, boulders and rivers. We refer to other members of the living world with the same language that we use for our family. Because they are our family.” [1]

***

Note: Despite Kimmerer’s teaching, this essay was originally full of ‘it’ and ‘its.’ Maia[2] felt the objectification and neutralization of animate beings and advised me. A few passes to make the changes and the tone changed. Thank you, Maia.

***

English is full of distinctions and judgments. We sort, compare, and rank. We compete, we battle, we want victory, we want to best. When English developed about 1000 years ago, hierarchy was a given. Hierarchy implies power and conflict. I looked up synonyms for hierarchy. I found ‘pecking order’ and ‘chains of command” Ah yes, the chains ….The consequences of an embattled mind are everywhere.

An example:

English displays a fundamental anxiety about gender that is prevalent in the culture – the battle between the sexes. In the most common areas of discourse, we are continually uncomfortable. Using the masculine as a universal creates hierarchy. As continuously citing both genders is cumbersome, the domination of men over women reigns. Alternating male and female becomes awkward and is not yet a grammatical solution. We need pronouns to represent male and female and the vast spectrum between them, the innumerable combinations, which manifest as wondrous realities. We need words for what brings us together, genders and species, instead of what sets us apart. The mermaids, mermen, silkies, winged angels, centaurs, bird women, the many bodied gods, Ganeshas, the myriad shape shifters, don’t they all point to existent forms of being that will enrich us if we allow them back into our sight?

What English does give us is a love of metaphor. We can build on this.

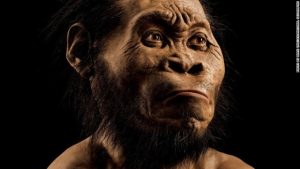

A startling discovery of a formerly unknown species, now named, Homo Naledi was announced this week, September 10, 2015. In trying to rank these beings, scientists are guessing they lived 2.5 million years ago. Two and a half million years ago. Why does this rephrasing make a difference? I think it does. The research teams think the species were of a branch in our “evolutionary” development that didn’t make it. (Died out. Didn’t become us.)

In some ways, they seem human: a foot nearly identical to ours, similar facial features, elongated limbs and hands that suggest the ability to carefully manipulate objects. But in other ways, they seem firmly australopithecine: curved fingers resembling tree-climbers’, an apelike trunk and a very, very small brain.[3]

The climb into the cave where they buried the dead is beyond daunting. There they left us a huge cache of bones. Thousands of fossils. Old and young people, women and men. They buried their dead! They buried their dead so well, the remains are well preserved even to this day.

Can I step out of my mind long enough to imagine they did, indeed, deliberately leave us the cache? That these bones are their conscious gift and communication to a species they hoped would find them millions of years later? Their gift rendered from dream, divination, even the guidance of spirit?

Why do they awaken us now? At this time, when we are warring against all life? What are they here to teach us? Click on the article. Look at the photograph of a constructed face. Relinquish your assumptions about hair, jaws, forehead.

I see a man peering far into the future. A seer.  He is not happy with what he sees. He is thoughtful and grieved. I think he sees us and that we have gone off the path. A being, who knows life, seeing it come to an end.

He is not happy with what he sees. He is thoughtful and grieved. I think he sees us and that we have gone off the path. A being, who knows life, seeing it come to an end.

Rather than rank these ancestors, let us imagine the ways they thought and felt about the dead, the rituals and ceremonies they performed, the hopes they had.

Or if you want to know about mourning ceremonies and the dead, observe elephants. If we don’t kill off this companion species, who should be sitting in circle with us, they will teach us. Despite our horrendous behavior, they act kindly to us – unless we do them direct harm. If we do harm, they learn of it from each other, even many, many miles away, and they remember.

Further, when they experience what our young ones experience in our all too common ghettos, when they lose their habitat, when their elders are culled before their eyes, when they lose their culture, when they are hungry and hunted, they turn on each other, on other species, even commit sexual abuse, otherwise unprecedented.

***

We are educated and socialized, both wisely and unwisely, by our ancestors, cultures and languages. What is male, what is female? We really don’t know. What is animate what is inanimate? Again, we don’t know. Color? Red, yellow, black, white. Black and white. Dark and light. Night and Day.

Racism, common to western culture, results from many embedded attitudes, including the culture’s current anxiety about the dark, which, in language, is opposed to light. We say, “These are dark times. Or it was a black day. She got a black mark…” Or, “Protect yourself with white light.” Opposition is not a useful way of organizing thought. One can as easily observe how varieties of light and dark intermingle to create the spectrum from the day sky to the night sky. Western culture’s focus exaggerates polarity while other cultures, and so languages, focus upon diversity, complexity and the benevolent consequences of relationship.

(I had to insert benevolent, otherwise, dire consequences, as in repercussions might be presumed. Consequences need not be negative. Another example of attitudes hidden in language.)

Western culture assumes superiority, assumes a divine and political right to dominate other peoples, political and religious systems, also the earth and all creatures. English is one weapon. Western culture also assumes everything is here for human use. Climate change is a direct result. Values, embedded in language, help sustain power.

When westerners separated themselves from the natural world, savage, an adjective, became a derogatory noun, demeaning Indigenous peoples, and by extension, making it morally feasible to war against, to enslave, to rape and plunder, to torture, to confiscate land and property, to kill.

Here is the progression, however:

mid-13c., “fierce, ferocious;” c. 1300, “wild, undomesticated, untamed” (of animals and places), from Old French sauvage, salvage “wild, savage, untamed, strange, pagan,” from Late Latin salvaticus, alteration of silvaticus “wild,” literally ” of the woods,” from silva “forest, grove” (see sylvan). Of persons, the meaning “reckless, ungovernable” is attested from c. 1400, earlier in sense “indomitable, valiant” (c. 1300).[4]

So the wild is associated with violence, and the non-western, the Indigenous, is cast as dangerous. However, the activities associated with savage are actually increasingly endemic to western culture, which is, if I persist in using the term, becoming increasingly savage, unrelentingly violent and inclined to appropriation and domination. It has been so for thousands of years – but increasingly so now. When we reference savages, we are actually referencing ourselves, but unconsciously, so savage becomes a projection. A possibility of a literature of restoration calls us to self-scrutiny. Because the true qualities, not judgment, of savage are to be emulated, in deed.

Few, if any, animals live in the ways that the word, savage, implies. The act of killing another animal in order to eat is, necessarily, aggressive, but animals are not violent by nature. Animals do not kill for pleasure or amusement like members of Western culture. Killing is not an animal leisure time activity, nor are animals entertained by watching each other fight and suffer. Nor do animals engage in endless war.

In 2012, I observed a young male lion walking quietly by the river among a herd of antelope and other prey. Presumably he was not hungry. All were peaceful with each other in their common territory.

In 2012, I observed a young male lion walking quietly by the river among a herd of antelope and other prey. Presumably he was not hungry. All were peaceful with each other in their common territory.

As neither animals nor Indigenous people, in the vast majority, are violent or dominating, we understand that savage and brutish are derogatory terms arising out of fearful, power hungry, distorted responses to the natural world. Whatever warrior codes Native American tribes may have had were limited in ways Western imperial culture does not understand. Native Americans, Indigenous people did not follow ‘slash and burn’ or ‘shock and awe,’ nor did they engage in perpetual war. Still, until only a few years ago, we did everything we could to prevent the Indigenous from speaking their own languages. They were forced to learn the language of the conquerors . This was called civilizing. They had to become savage.

“Kill all of the brutes,” is the phrase King Leopold used when conquering what became the Belgian Congo. With these words and the cruel attitude fixed in them, colonization devastated and subsumed Africa’s resources, environment, animals and people. The horror of the Democratic Republic of Congo – rape, pillage, torture, child soldiers … — is directly attributable to the colonial activities of Portugal, Belgium, France, the English, later Americans, Chinese, Japanese … the rape, pillage and torture of all of Africa by various non-African military, missionaries, merchants, miners, industrialists exhibiting ravaging hunger for minerals, resources, land and power. This violence against all beings, which did not exist before the overt and subtle occupations, continues to this day. We can suppose the various African people were not civilized enough to develop such violence and carnage as we have brought.

Having said all of this – the negative implications of savage and brutish remain, hurled at one group or another, as I have also done above, still implying that the human or some humans are superior to others or to the animal, that the civilized is preferred to the wild. So while we are working so hard to rewild the world, and are questioning whether civilization is civil, let’s just drop savage and brutish … they don’t help us restore a livable word and find or develop language that sees the world differently. Not easy. Needs all of us to participate, each in our own particular and peculiar way, and together, not seeking consensus, seeking council / circle mind.

***

For different peoples, particularly Indigenous people, animals, other beings of the natural world are sacred, are spirit beings, who connect us with wisdom and the holy. The languages that develop from such Indigenous perceptions and values transmit a distinct appreciation of the natural world and the nature of human and non-human beings. If only all of us could learn an Indigenous language, we would become far wiser, even by incorporating the structure, as we become fluent. The structure of language – the structure of our minds.

Indigenous cultures, based upon reverence for the earth and the complexities of inter relationships between all beings are … [Now I run out of an ability to communicate clearly in English.]

… are far more, civilized, referring to civil society, the State and the public life? Urban life is rarely as kind, compassionate, caring as tribal societies. Are far more developed? From the earth’s point of view, and the perspective of many others, development undermines the natural world and creates dangerous hierarchies.

What appropriate words of praise shall we use to finish that sentence? The words we might automatically consider – like powerful, successful, noble, only reflect English’s assertion of what is good and important. Beliefs we assume to be human and universal are frequently simply particular to the language spoken. But the dominant culture, and its values, has brought us to this time of dread and destruction.

What really matters? What might lead to a viable future? A language, a literature of restoration, calls each of us to consider the steps that might bring us there and find the words that will carry us. So it is for each one of us to try to finish the sentence above by intimately considering the fate of all beings and speaking from the broken heart.

In order to finish the sentence above, I have to stand in a forest before a circle of elephants who are mourning the horrifically painful death of an elder, hunted by helicopter, felled by AK47s, whose tusks were cut out of his face as he was still alive. His tusks have become cigarette holders. On the other side of that image, is a word that by its presence would forbid such action, because Indigenous wisdom forbids it. I don’t know what the word is … but I will wait rather than write something without that moral suasion.

***

A Yakama Elder was reflecting on the Yakama language and why Yakama could not be translated into English. He is against dictionaries and on-line language courses because they give the illusion of translation while becoming unwitting vehicles for undermining and limiting the people’s culture. Unless one sits with and at the feet of those who learned the language as children, who learned the rhythms, sounds, the subtle intonations, the music that shifted meaning, also the songs, chants and prayers in the original language, one doesn’t know what one is able and unable to glean and understand, he said.

The man who was speaking about this, was not speaking abstractly. He has devoted his life to addressing the problems of environmental restoration and toxic waste for his community, a confederation of tribes in the Pacific Northwest. He spoke personally about the Hanford Nuclear Site on the Columbia Gorge. The territory for this site where plutonium was manufactured, was seized by the US government through eminent domain from Yakama sacred land. He told us that his uncle was released from prison in return for submitting to a medical experiment. Strontium 90 was inserted in his testicles. He died two weeks later.

I couldn’t know what he said when he blessed the meal we were sharing. I watched his face, listened to the music in his words, saw that he was taken by prayer, trying to imagine how this might occur in English and so learn from him by listening outside of translation.

My friend and land mate, Cheryl Potts, said she had wanted to learn Alutiiq, her native language, on line, but each time she tried, she had to withdraw. She could not convince herself that there was a true transfer of meaning from Alutiiq to English. She thought she might learn some vague equivalents, but they would not include the essence, the spirit. The loss, the lacunae was great.

English can encompass only what is resonant and understandable from another culture, which given the great discrepancies between English and Indigenous wisdom, is minimum. There is no way for English to incorporate Spirit when translating. Inevitably the spiritual essence will be removed the way the Indigenous culture was suppressed. Another means through which the Conquest persists.

Yet, the presence of Spirit may be intrinsic to each word in certain Indigenous languages, in the way motion and action are intrinsic to every word in Navajo. Verbs, not nouns. Movement not objects. Movement – the life force. Spirit in the structure of the language.

Tzutjil Maya is a language of flowers. The language is a gift, a bouquet of poetry that the speaker offers a lover and /or the community. Maybe such languages of vitality, like Navajo, Yakama, Alutiiq, Anishinaabe, Tzutjil Maya are incapable of supporting the development of the technology of death which arises so easily from English and Indo-European languages.

Every war we fight, win or lose, every misappropriation of earth and the natural world, survives in language and literature, until finally war and extinction have become the condition of existence that should be grounded in the life force. The war against nature, the war against illness, the drug wars, the Indian wars, the gang wars, the race wars, the gender wars, the war to end all wars, the kinds of weapons we develop and the kind of wars we fight…. Have we come to a time when we, unwittingly, make war whenever we speak? How shall we sweeten our words so they do not march us toward perpetual war and extinction?

Where is the honey we need? Will it come to us if we continue to kill the bees with our pesticides? It’s time to refresh the Buddha fountain so the bees can drink.

When the NGO, everyday gandhis, visited villages in Liberia to sit in council around joint grass roots, peacebuilding activities, we became aware that discussions could not continue for too long without the people breaking into drumming and dance. This was not for relief. It was another form of contemplation and communication.

It’s hard to understand that dancing and drumming are forms of prayer until you give yourself fully to the divine. Then you can feel the body calling down the spirits because it is so lonely without them. And if your language doesn’t let you call to them in the ways we must in such a time, then you raise your hands and move your feet in prayer.

I saw this at the NGO forum of the UN Council on Women in Nairobi in 1985. Gather on the lawn whenever you can, morning until night, drum and dance. Let the younger women open for the older women who come into the circle when it is time for the spirits to descend.

So let’s stop here and have a few quiet moments and offer prayers that we may, over time, find the words to sustain all life.

***

The Anthropocene describes the moment in geologic time when humans began affecting the environment. Thoughtfully used, it calls us to responsibility and heartbreak.

Donna Haraway writes,

Perhaps the outrage meriting a name like Anthropocene is about the destruction of places and times of refuge for people and other critters. I along with others think the Anthropocene is more a boundary event than an epoch…. The Anthropocene marks severe discontinuities; what comes after will not be like what came before. I think our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/thin as possible and to cultivate with each other in every way imaginable epochs to come that can replenish refuge.

Right now, the earth is full of refugees, human and not, without refuge.[5]

(I came upon the above at the time when the refugee crisis in Europe is creating havoc everywhere. While it is becoming clear that the crisis is directly related to the activities of the US and other countries in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and other countries, it is not yet blatantly clear that US and other imperialist policies are also responsible for the asylum and refugee crisis in Latin America.)

We need languages and literatures that do no harm, that offer refuge, that honor and sustain interconnection, community and the vitality of life – the survival of all beings, co-existence.

Living outside of a conventional, culturally determined language, creating worlds for ourselves and others that can take us beyond assumptions and restrictions, is difficult but not impossible. Contemporary speakers of English have the challenge of using the language to describe and communicate values different from the language’s fundamental assumptions. Can we begin to create a language and literature wise enough to engage in translation?

***

And so the writers….

A Literature of Restoration? Story is core, is at the heart. So is the natural world. So are all the non-human beings. And so are dreams and visions, the transmissions from the spirits, the invisibles and their invisible worlds. Equally important is the chronicling of the terrible pain and sorrow of so many of the world’s creatures and humans as well. Equally important is taking responsibility for the harm we have and are doing to the earth and each other.

How shall we create it? How shall we devote ourselves to praise, prayer, beauty and truth telling? Are we speaking about language here or literature? We can’t separate them. Just as we can’t separate the Congo from South Africa or Liberia or ourselves. Everything must come together in the circle of our understanding.

But we can step away from the linguist and cultural habits of materialism, the cults of brand names and celebrities, the reflex of objectification and the aggrandizement of technology, and other public forms of identity, power and status. We can respect individual experience, can weave dynamic webs of interconnection among humans, non-humans, time and space, past and future.

For the Literature of Restoration, myth can be a great truth, not a deception, and the heart is not a mechanical organ but the seat of intelligence. Such a literature finds peacemaking intriguing. Rather than valorizing the new over all, these works seek to restore the heart of the old, old ways, Indigenous and aboriginal wisdom ways and traditions that ally with creation. The Literature of Restoration can be an unimpeded literature that questions, bears witness, interrogates certainties, values imagination and the great unknown, the great mysteries. Hope is possible within the heart of Literature when focusing on what is truly life-giving and is committed, first and last, to a viable and beautiful future for all beings.

This is a call to those of us who care about the future to infuse English with those rhythms, sounds, meaning and resonances that restore the world by their very presence. As with Indigenous languages based on relationship, the Literature of Restoration asks and responds to the question of why we speak altogether. To restore language by creating a new literature altogether wherein plot, information, theory and content become less important as the possibility of the survival of the planet and all beings is affirmed by relationship, interconnection and presence. A literature that is connected not conflicted, intrigued by what brings us together rather than focusing on what sets us apart. A literature, saturated by beauty, deep respect for the earth, by the reality of the ancestors, the wisdom of the other beings and by awareness of the presence of the spirits, will not be the instrument that allows the kind of rage, destruction and violence that is endemic to western culture, but may be a form to restore creation.

Let us imagine writing and creating language at the same time. Imagine that the words we use can create relationships with all beings, earth, animals, elementals, plants and their spirits, and so can ease, restore and recreate our afflicted world. Imagine that the language we recreate communally, notwithstanding subject matter, can bind us together, can become life-giving. Imagine that our explorations into the subtle implications of the words selected, their implicit and explicit meanings, their associations, structures, references and rhythms, can create a field of understanding far beyond the content. The Literature of Restoration can be a gift that like the offering of tobacco, or speaking in council, prohibits lies, falsehoods and deceptions. A literature that speaks truth, speaks beauty.

We are called to share the stories we carry so that we can live within them. We need to speak the stories that shape us as a people and teach us how to live with the earth and each other.

We are called to story, to language and to enact the new, true, ancient, desperate beauty ways that we are called to live. We need to be with each other in the story, in community and language that describes and so creates the world for which we are longing. To live as outlaws outside of the conventions which confine and manipulate us, to find the words and wisdom from which we are separated in order to break our minds, as were African slaves and Native Americans.

Without a common language, without shared stories, without deep vision of the real nature of the world, there is no culture and so no community and so no power or possibility. Therefore, we are called to step out of conquest and the mind of conquest. Step out of oppression, out of actions against the earth. We are called to reimagine and revision language and literature as dynamic ecotones, and ecosystems supporting all life. Restore, revision and piece together the broken, burned shards of once vital histories, dare to know what we know, to see and understand with our hands and feet what is irrefutable, to listen to the ancestors and the future, to the dreams and the signs, old syllables and unborn orations, birdsong, whale song and howl, the glorious and tormented recitations of wind, water, light and earth, to bring together a luminous grammar of connection so that through such shared conversations and our own emergent literature and culture, we make ourselves places to live that can survive these times

[1] http://darkmatterwomenwitnessing.com/issues/Apr2015/articles/When-Earth-Becomes-an-It_Robin-W-Kimmerer.html

[2] http://darkmatterwomenwitnessing.com/issues/Nov2014/articles/Naming_Maia.html. She is also the author of the SpiritLife of Birds, Adder’s Tongue Press, 2012.

[3] http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/10/africa/homo-naledi-human-relative-species/index.html